CEO of a major UK semiconductor manufacturer wants the government to pour “hundreds of millions” into the industry.

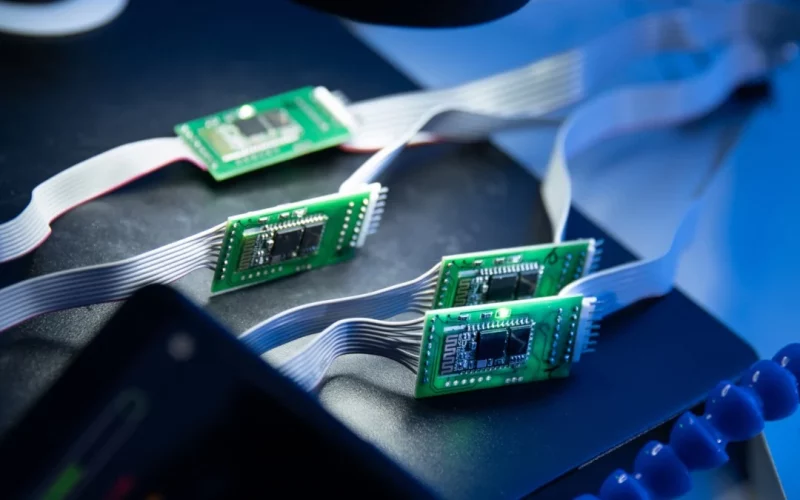

Microchips, also known as semiconductors, are essential to the operation of millions of goods.

Pragmatic Semiconductor’s Scott White warned that without a massive financing boost, UK companies would leave for foreign shores.

The government has promised to release its plan to increase the availability of resources like training and equipment shortly.

In light of a new report stating that the UK government “must act now to ensure the future of the important UK semiconductor industry,” this news comes as no surprise.

Pragmatic’s CEO, Mr White, said that “a few tens of millions of pounds” wouldn’t be enough to “move the needle” in the chip industry.

To “make a substantive effect,” the sum “has to be hundreds of millions, or even more than £1bn,” he said.

There should be no “unfair subsidies,” but rather a “level playing field” with other nations.

According to Mr White, the UK must “invest significantly” in its own microchip industry because other governments are doing so.

Between its Cambridge headquarters and its two production sites in County Durham, Pragmatic Semiconductor employs a total of 200 people.

Mr White continued, “that only makes sense if the economies are warranted compared to elsewhere,” clarifying the company’s desire to maintain production in the United Kingdom.

The Institute of Physics (IOP) and the Royal Academy of Engineering released a report on Thursday that says “skills shortages, high costs, and low public awareness threaten the UK’s position in the crucial semiconductor race” (RAE).

Recent years have seen a global shortage of microchips, which has temporarily halted production of everything from video game consoles to automobiles, prompting this research.

Both the IOP and the RAE have made a plea for increased funding for the industry in the United Kingdom.

The importance of the sector is also being highlighted, and they want to see more children encouraged to pursue science at school.

The government is urged to unveil its long-awaited national semiconductor plan in the report titled UK Semiconductor Challenges and Solutions. In fact, two years have passed since we first started working on this.

The UK can’t always depend on imports to meet its need for microchips, according to Louis Barson, the director of science, innovation, and skills at IOP.

A robust domestic semiconductor sector, he argued, is essential to national and economic security.

One assessment puts the worth of the semiconductor industry in the United Kingdom at $13 billion (£11 billion). According to estimates, the worldwide value of this sector is closer to $580bn (£490bn).

At the same time, a study presented to parliament last fall stated that the United Kingdom contributed only 0.5% of the world’s semiconductors.

The Institute of Physics estimates that there are presently around 40 semiconductor companies in the UK, with 25 engaged in manufacturing. In addition, it predicts that there are approximately 11,400 individuals employed throughout the entire organization.

Some recent developments in the UK have been ominous for the sector.

The chip design company Arm, which is based in the UK, said last week that it would list its shares on the New York Stock Exchange instead of the London Stock Exchange. The announcement was made despite Prime Minister Rishi Sunak of the United Kingdom meeting with executives from SoftBank of Japan, the parent business of Arm.

Furthermore, IQE, another UK chip company, has already warned it may have to move overseas if the government does not provide more support for the industry.

This occurs as governments around the world spend heavily on the semiconductor industry. The United States government committed $50 billion over the course of five years to the sector last summer. This included $29 billion for increased output and $11 billion for R&D.

Brussels in the European Union has identical plans, allocating €43 billion ($46 billion; £38 billion).

“Other countries are continuing to invest heavily in their own semiconductor industries, and the UK will fall behind without timely government action and a coherent strategy,” said Prof. Nick Jennings, head of the RAE’s engineering policy center committee.

The IOP and RAE want the government to affirm that it will move forward with its proposed plan to set up a national body for the sector, a so-called “semiconductor institute,” regardless of the financing situation.

Importantly, it could “speak for the sector,” providing a “coordinated voice” that would enable the industry to “present a united front,” as Mr Barson put it.

According to a government spokesperson: “Our upcoming semiconductor plan will detail how we will help the industry gain access to the personnel, infrastructure, and technology it needs to thrive. When the time is right, we will release the plan.”